Happy Monday! This week was all about TLC. Not the 90’s girl band, nor the acronym ‘tender loving care’, but rather a bit more wine science. Today I am writing this post from a bumpy little bus on the way to Ararat for a spot of last-minute pruning, so please excuse any blips. The chance to hone my skills was too good to miss and I am doing my best to make the most of the journey for study.

Top 2 things I have learnt this week:

1. More than a flavour

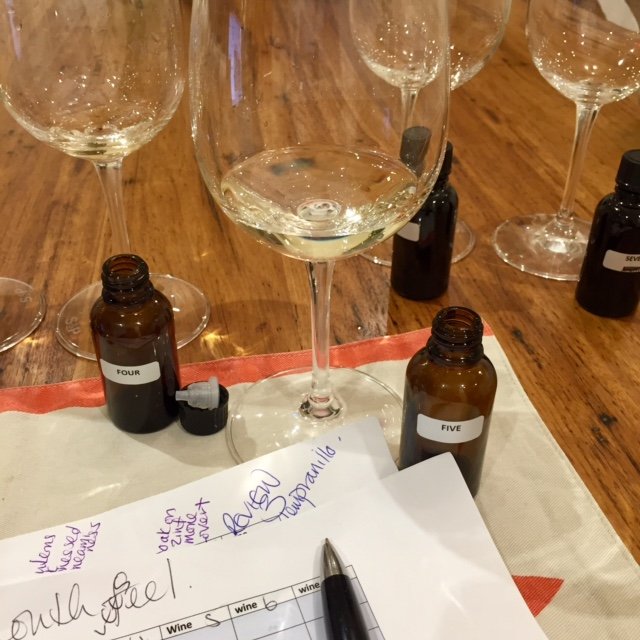

Our wine evaluation session this week saw us looking beyond the flavour and aromas of the wine. Previously, I have mentioned that good wine has the perfect balance of sweetness, acidity, alcohol, tannins and flavour. The first four members of this list contribute to more than just the flavour of the wine. This week it was all about the ‘mouthfeel.’

Our wine evaluation session this week saw us looking beyond the flavour and aromas of the wine. Previously, I have mentioned that good wine has the perfect balance of sweetness, acidity, alcohol, tannins and flavour. The first four members of this list contribute to more than just the flavour of the wine. This week it was all about the ‘mouthfeel.’

Body: Full-bodied, light bodied… terms to describe one aspect of mouthfeel. Full bodied wines are often higher in alcohol and tannins and can be described as ‘mouth filling.’ On the other hand, light-bodied wines are more like water on your tongue and have a more localised effect.

Roundness: Another way of describing the feel of a wine in your mouth. Alcohol and sugars can give rise to a roundness in wines. Roundness can be felt like a slight viscosity or, as I like to think about it, a blanket for your tongue. I am a bit of a romantic.

Astringency: Tannins, acid and alcohol can all contribute to astringency – but mostly tannins. Have you ever had a wine that actually feels like it dries out the sides of your cheeks? That is astringency and it is often caused by the tannins (of red wine) reacting with the proteins in your saliva and changing its consistancy. If you spit an astringent wine after swirling in your mouth, you will see these protein-tannin complexes as stringy deposits. Lovely.

Heat: Alcohol and acid contribute to the heat of a wine. High alcohol wines have a warming effect, which can either be felt in the mouth or after swallowing.

All of these factors play a part in how your wine feels as well as tastes – look out for them next time you have a Pinot Gris, Oaked Chardonnay, Nebbiolo or Shiraz.

2. TLC – Thin Layer Chromatography

Wine samples spotted onto plate

Plate dipped into solvent

Malolactic fermentation; I feel like I mention it a lot. Its a secondary fermentation, carried out by bacteria, during which malic acid (sharp green apple taste) is turned into lactic acid (softer, buttery taste). It happens naturally in most wines, especially reds, but is prevented in some aromatic whites like Riesling. Carbon dioxide and a whole host of other flavour compounds are produced, which can be good and bad. It is essential that winemakers stay in control of this fermentation and they can check its progress by two methods.

Plate dipped into indicator

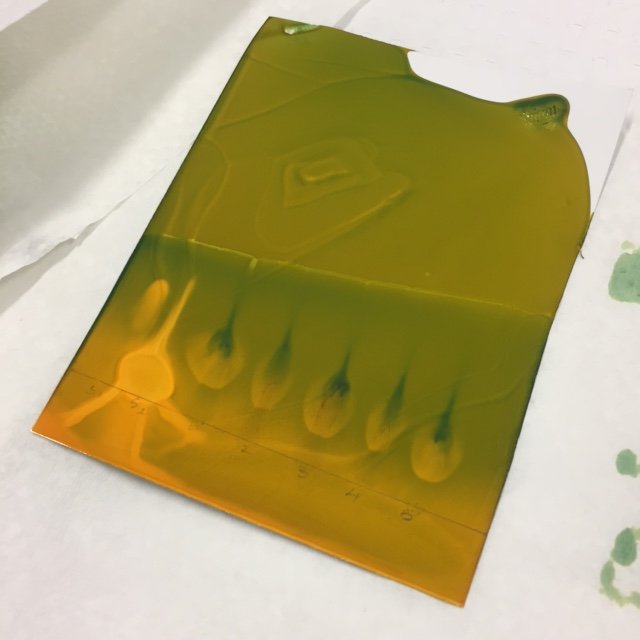

TLC, is the method we got to play with this week in Wine Chemistry. This colourful form of chromatography is a method used to separate the organic acids in a sample. Wines are spotted onto a silica plate along with some pure samples of the acids in question. The plate is then dipped into a solvent, which moves up the plate carrying different components at different rates along with it. Just like that experiment you did with pens at school!

Plates dried

Acid spots show up as yellow – this did not work well for the samples

The aim is to separate the malic and lactic acids. After processing with an indicator, blobs level with the malic acid standard indicate the presence of malic acid. Blobs level with lactic acid indicate the presence of lactic acid. Conclusions can therefore be drawn about the occurrence of MLF. A result showing a lactic acid blob only indicates full MLF has occured and no malic acid is left.

This did not quite work as we hoped – our smaples were rather old, but we got the picture. I hope you can.

The rest:

We were left to our own devices this week for vineyard management and I started to plough through the mass of write-ups required of last weekend’s practical sessions.

One of my peers is Vineyard Manager at Stonier on the Morning Peninsular. I bought a couple of bottles of Pinot off him this week – the 2009 and 2012. We enjoyed both with friends over the weekend. Trying different age wines from the same vineyard is so interesting. Though their underlying fruit characters were very similar, everything else, from the appearance to the other flavours were different. This highlights the variation that time and perhaps climate can give a particular vintage. Try it!

This week is the semester break so I’m off to the Grampians for some pruning before enbarking on a chemical handling course at Yan Yean. Stand by!

As ever, thank you so much for reading…