Viticulture rocks! The more I learn about the cultivation of these ancient plants, the more fascinated I become… Winemaking was always my first goal, but I am delighted to discover an affinity for the vineyard itself.

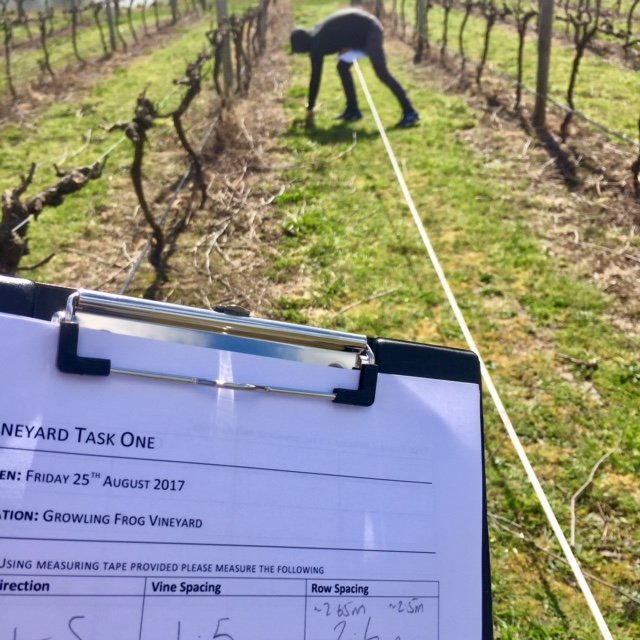

Friday was spent back at Growling Frog vineyard for a spot of field work focusing on vine density and vineyard topography. It was a long week, ending midday on Sunday, following a full-on weekend workshop for Vine Physiology and Grape Production (mostly taught online). Best of all, when you get to meet your fellow course mates face-to-face, is the chance to learn from the collective experiences. We are all from a wide range of backgrounds with different aims. Many of my peers are already working successfully in the field.

Most of the week however, was less about the actual field (or vineyard rather) and more about the books. Lots and lots of reading with a touch of tasting to keep us truly focused on the prize!

Top 3 things I have learnt this week:

1. Sauternes – yes please!

Not usually one for sweet or fortified wines – unless there is A LOT of cheese involved, I am least excited about tasting these wines. This week I had to suck this up and get on with tasting a flight focused on wine sweetness. Not quite as unpleasant as I had imagined, amidst the pack I discovered a true gem: Sauternes!

Sauternes is a sweet wine made primarily from the rare white Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc grapes grown in Bordeaux. Bursting with ripe fruit flavours including: Sweet lemon, apricot, tropical fruit and honey, this noble wine relies on another bloom of microorganisms. Botrytis is a type of rot (often referred to as noble rot). Infections are common in thin skinned grapes like Semillon, and though not always as welcome, the rot shrivels the berries concentrating the juice. Botrytis infected grapes typically result in gold-coloured sweeter wines with flavours of honey, apricots and orange.

Delicious! The complexity of the aromas, well balanced sweetness with high acidity and long finish was delightfully moreish. Look out for it! Smashing with blue cheese, it will cost you around $30 for a decent 375 mL bottle.

2. Soft pruning

Over the weekend, I had the privilege of hearing one of my classmates, and the Vineyard Manager for Stonier (Mornington Peninsular), speak about a new pruning technique. Previous entries have mentioned the types of vine pruning and ways they are used to manipulate fruit yield etc. Well, I was not expecting to add another one, but I am going to do my best to sum it up for you…

What is involved?

Every time a cane is cut from a vine, the open wound needs to heal – much like we do. Open wounds are susceptible to pathogens and disease – just like with us. Though it may not be evident for some years following pruning, poor practices can result in stress to the vine, which will eventually lead to reduced fruit yield or irreversible die-back.

Vine healing involves the drying out of the wound, and if the incision was made too close to the trunk or cordon this results int he formation of a desiccation cone. These cone-shaped areas of dry wood can impede the sap flow through the vine, causing it to divert. A diversion of sap flow can increase the water pressure through the vine, making it work harder and diverting energy from the canopy or crop.

Soft pruning hinges on creating a balanced sap flow through the vine and reducing the introduction of desiccation cones. Techniques included cutting the vine with 90 degree cuts, rather than cuts on an angle. These cuts are made far enough from the trunk to allow for die-back or through a basal bud for the same reason. It is much more complicated than that… but I was fascinated. In a nut shell – if you stress your vine then it will not have the energy to channel into the lovely fruit and more importantly – your wine!

3. Field work etc.

As you can imagine, with a weekend of field work and work shops my head is swimming with extra information. We found ourselves tramping around a vineyard, measuring vine separations, row widths and counting missing vines. Mostly the exercise was to enable us to reflect on the importance and relevance of sampling when making assessments about a vineyard.

As you can imagine, with a weekend of field work and work shops my head is swimming with extra information. We found ourselves tramping around a vineyard, measuring vine separations, row widths and counting missing vines. Mostly the exercise was to enable us to reflect on the importance and relevance of sampling when making assessments about a vineyard.

Climate considerations, topography (the shape of the land) and viticulture techniques all influence the layout of a vineyard. Vineyards are different all over the world and once again there are no set rules. On average, Australian vineyards have individual vines planted 1.5 m apart and rows around 2.7 m apart. (2000-2400 vines per hectare). Fruit zones are usually set to around 90 cm above the ground. Conversely, in France, vines are much closer together, as little as 1 m. The inter row spacing can be vastly reduced too, as a result, vine densities are between 300-10000 vines per hectare. The vines there tend to be a back-breaking 70 cms from the ground too.

There are many theories and practicalities influencing the deign of a vineyard including:

- Use of large machinery

- Frost risk

- Appellation style

- Disease pressure

- Air flow

- Fruit quality

Not sure I’d like to be pruning some of those vertically challenged little vines!

Time for anything else?

Glucose in Play-Doh, workshop activity

Fructose in Play-Doh, love it

As well as school, I have had the chance to try some lovely wines this week. I needed to review a Tempranillo from Kelleske, Barossa Valley (I will post these reviews soon). I also enjoyed a bright young Fiano from Rabbit & Spaghetti – see my Insta feed.

Next week is the final week before our semester break. Though I always seem to have my head in a book, I need to catch up on some reading. On Friday I have the second Wine Chemistry practical workshop. We will be carrying out some thin layer chromatography to test for the completion of malolactic fermentation (secondary fermentation). I’m such a nerd, I’m already excited!

We are hoping to attend a wine event in the city on Saturday and I need to review a cheaper Italian Prosecco for Wine Evaluation. As a result, I hope to have more lovely wine to talk about.

Thank you so much for reading – see you next week.