Just a quicky from me this week as I was mostly expanding my knowledge of terroir from home. I handed in my first literature review draft (it was horribly over the word count as per – well, I’m a chatter box!). I got an A (yay!) and a B (boo) for wine evaluation – in a review I forgot to state that the white Burgundy we tasted was Chardonnay, tut tut. I’ll post the review though – the wine was delicious. Extracurricular activities included a barrel tasting with our chums at Noisy Ritual and a sample of our own Shiraz.

Top 3 things I have learnt this week:

1. Acids in wine

This week in Wine Evaluation we were looking at the effect of acids in wine. Acids are important in wine for a number of reasons:

- They contribute to flavour, as they have specific favours of their own (malic – green apple, lactic – soft/milk)

- They contribute to the balance of a wine along with sweetness, tannin and alcohol

- They are involved in biochemical reactions that result int he expression of other flavour compounds

- They affect the wine colour (high acid – bright or red, low acid – dull, purple)

- They contribute to stability and longevity of wine by preventing oxygen and microbial spoilage

The way I have learnt to assess of the level of acidity in a wine is to swill it around my mouth and, after spitting, see if my mouth waters. The more mouth-watering a wine is, the more acid it contains. You might be surprised too. Some wines may not appear on first sip to be very acidic, but they may contain lots of acid which is well balanced by some residual sweetness. Often sweeter wines are deceptively acidic. It is all about balance when producing a good quality wine.

2. Terroir – soil

Last week I mentioned root-stocks, with most of the world now planting Vitis. Vinifera (lovely wine grape vines) grafted onto alternative American Vitis species. The purpose of this rather pricey practice is to convey resistance to pests like phylloxera and nematodes as well as drought and lime (high pH). In Vineyard Management this week, we expanded on this by looking at some particular rootstocks and the terroir they are most suitable for.

Vines are pretty hardy plants that will grow in a wide range of soils – and wow, there are wide range of soil types on this planet! However, if your aim is to grow top quality fruit that reflects its terroir, then the soil is VERY important. Too fertile and your canopy vigour is going to be out of control – resulting in loads of leaves and some pretty well shaded low yields. Too hard and the roots will not be able to penetrate. Too dry risks the fruit shrivelling – though it is widely thought that a bit of water stress is good for fruit quality. Too sandy and you risk erosion and a lack of nutrients, too heavy and you risk water-logging. You get the gist?!

When the soil is just right, for example, in Marlborough, NZ; gravelly clay based soils with clay/loam subsoils, it is reflected in the wine. The particular wine I am referring to is Cloudy Bay Pinot Noir, which attributes (in part) its primary fruit aroma (cherry and plum) and boldness of character to the soil terroir. Full review notes coming soon.

3. Designer bugs

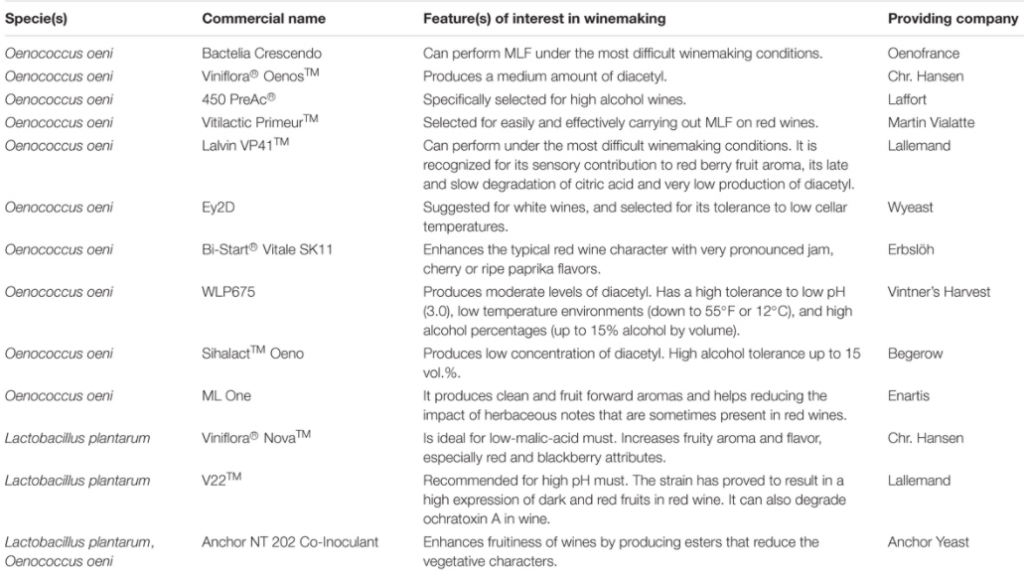

Whilst writing my literature review on malolactic fermentation (MLF) – the secondary fermentation in wine carried out by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) converting malic acid (sharp apple) to lactic acid (softer/milk), I found this table:

Cultured bacteria available for MLF (Leonardo et al., 2017)

The table lists a number of cultured bacteria available for winemakers to induce MLF. MLF does occur naturally in most wineries, but it can be a little unpredictable with both positive and negative results. Not only is lactic acid formed by these little bugs, simultaneously a whole host of other biochemical cascades are set in motion that can seriously affect the organoleptic profile (smell, taste and mouthfeel) of the wine. Staying in control of this is key to making quality wine.

Technology has enabled scientists to attribute the synthesis of certain flavour molecules to specific species of bacteria. Now winemakers can select the bacteria they want to carry out MLF based on the desired aroma effect. This is just the tip of the iceberg too. By the time they are thinking about which bacterium to use, they have probably already completed the same process with yeast during primary fermentation. There are even more designer yeast available for a similar purpose. So next time you taste a particularly aromatic wine, spare a thought for the microbeasts that may have contributed to your glass.

Onward and upward…!

Next week I will try and improve my wine reviewing by remembering to always state the varietal. I reviewed the Pinot Noir mentioned above. I am in uni for three days, with two workshops and a lecture, so should have lots to report back on. Another hectic weekend with friends is planned – so I am sure I will have lots of wine to review too, yippee! Thank you for reading.

If you ever want to ask me any questions about my little articles or have any comments please email me at andi@classtoglass.com

LEONARDO, P. et al. Microbial Resources and Enological Significance: Opportunities and Benefits. Frontiers in Microbiology, Vol 8 (2017), 2017. ISSN 1664-302X. Disponível em: < https://libproxy.melbournepolytechnic.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.1cef5061dace4b17876978a920acdae0&site=eds-live&scope=site >.